This year marks a sad anniversary in Red Sox history. Fifty years ago, rising star Tony Conigliaro was brutally struck in the face by a fastball, a tragic event that changed the trajectory of his highly promising career.

For those too young to know, “Tony C,” as he was known, started his career as brilliantly as any player in club history.

Born in Revere, Massachusetts, Conigliaro graduated from St. Mary’s High School in nearby Lynn in 1962. The Red Sox immediately signed the 17-year-old right out of high school and he made his major league debut just two years later.

In his first game at Fenway, on April 17, 1964, the 19-year-old, local product hit a towering blast that cleared the Green Monster. It was a sign of things to come. Tony C enjoyed a sparkling rookie season, batting .290 with 24 home runs and 52 RBI in only 111 games. To this day, he holds the Major League record for most home runs hit as a teenager.

Unfortunately, Tony C’s season was cut short due to a broken arm. The injury may have cost him Rookie of the Year honors, which instead went to Minnesota's Tony Oliva.

The next year he hit 32 round-trippers, becoming, at the age of 20, the youngest home run champ in American League history. That year, he also slugged .512 and drove in 82 runs in just 138 games.

Tony C was already becoming a folk hero by the time the 1966 season rolled around. As a 21-year-old, the right fielder hit 28 homers with 93 RBI. He was a bona fide superstar in Boston.

As his teammate Rico Petrocelli said of him, "Conigliaro had it all: tremendous talent, matinee idol looks, charisma and personality.

That combination of assets earned Tony C a recording contract and he actually cut a few records. He was a guest on TV shows, such as the Merv Griffin Show. Conigliaro’s fame extended well beyond the baseball diamond.

Ih his book, “Tales from the Impossible Dream Red Sox," Petrocelli said this about his friend:

An eligible bachelor, Tony C. was easily the most popular player on the Red Sox, especially with the ladies. He certainly took pleasure in their company. But while he dated actresses and Playboy bunnies, he wasn’t a playboy… Tony didn’t like to go to fancy nightclubs. In fact, he preferred to stay out of the public eye as much as possible.

In 1967, the 22-year-old continued his torrid pace and made his first All Star team. Through August 18, Conigliaro was hitting .287, with 20 home runs, 67 RBI and a .517 slugging percentage.

Then, tragedy struck when he was hit in the face by a fastball from Angels’ pitcher Jack Hamilton. It changed the course of Tony C’s skyrocketing career and may have ultimately cost the Red Sox the World Series that year (Bob Gibson notwithstanding).

Despite his season being cut short once again, Conigliaro became, and remains, the youngest player in American League history to hit 100 home runs, reaching the century mark at 22 years and 197 days. Mel Ott, was the youngest player to hit 100 home runs and his was the first National Leaguer to hit 500 home runs.

A promising, possibly historic career was forever changed by Hamilton’s misfired pitch, which hit Conigliaro squarely on the left side of his face.The pitch broke his left cheekbone, dislocated his jaw and severely damaged his left retina, resulting in 20/300 vision.

Petrocelli swore that the noise the ball made when it impacted Conigliaro's face could have been heard clearly all over Fenway Park, which was near capacity that Friday night. He said it sounded as if the ball had struck Conigliaro’s helmet, but it was the sound of his face being shattered.

Conigliaro lost consciousness and lied listless in the batter’s box. His teammates gathered around him in horror. His skull swelled up like a ballon. Blood poured from his nose. Petrocelli said he thought his friend would surely lose his left eye. Three teammates lifted Tony C’s limp body onto a stretcher and carried him off the field.

Conigliaro later said he thought he was going to die.

Dr. Joseph Dorsey, who examined the slugger at Sancta Maria Hospital in Cambridge, said that if the ball had struck Conigliaro an inch higher and to the right, he might have indeed been killed.

At the time, hitters wore batting helmets without the earflap that is customary today. Had he been wearing a modern helmet, things might have turned out quite differently.

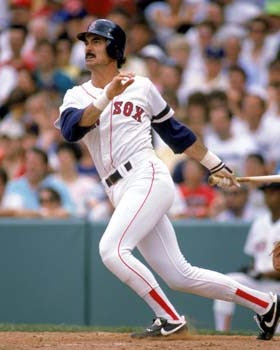

Hamilton, the Angels' pitcher, tried to visit Conigliaro in the hospital the next morning, but was denied admittance to his room. Few visitors were allowed and the press was barred from interviewing him, but a photographer was permitted to snap the iconic photograph above.

The young slugger’s sight was permanently altered and he missed the entire 1968 season.

Though he returned in 1969, batting .255, with 20 home runs and 82 RBI, his left retina had been irrevocably damaged. Still, he won Comeback Player of the Year honors and got to roam the outfield alongside his brother, Billy, who played with the Red Sox from 1969-1971.

The 1970 season proved to be an extraordinary comeback for Tony C, as he hit .266, with a career-high 36 homers and 116 runs batted in.

The performance earned him the Hutch Award, which is given annually to an active Major League Baseball player who best exemplifies the fighting spirit and competitive desire of Fred Hutchinson, a former big league pitcher and manager who was stricken with fatal lung cancer at the age of 45.

Perhaps the Red Sox organization knew that Tony C’s best days were behind him. Perhaps it was his uneasy relationship with manager Dick Williams. Whatever it was, Boston traded Conigliaro to the Angels after the 1970 season.

His eyesight worsened and the effects were obvious. Petrocelli said that his former teammate could barely see out of his left eye. Conigliaro played in only 74 games in 1971, hitting .222, with just four homers and 15 RBI, before going on the disabled list in July. He retired at the end of the season at the age of 26.

After four years away from the game, Tony C attempted a comeback with the Red Sox during the 1975 season. Though he was still just 30-years-old, Conigliaro was s shell of his former self. Over 21 unmemorable games, he batted .123 with 2 home runs, before retiring for good.

Conigliaro never fully recovered from the horrific beaning he suffered in August, 1967. It derailed his brief but brilliant career. If you exclude the aborted comeback in '75, Tony C played just seven seasons in the majors, two of which were under 100 games. We’re all left to imagine what might have been.

Conigliaro hit 162 homers during his relatively brief career with Boston. Baseball historians, and Red Sox fans old enough to remember him, are left to wonder what he could have accomplished over the course of a 15 or 16-year career. Many believe he surely would have been a member of the 500 home-run club. After all, he had already eclipsed 100 homers by the age of 22.

Food for thought: Mel Ott, the only player to reach 100 homers at a younger age, is a member of the 500-hume run club.

Consider that Conigliaro hit 104 homers in his first four seasons, from the ages of 19-22. In that span, he averaged 26 homers. Meanwhile, he never played in more than 150 games over those four seasons and averaged just 124 games.

Had he averaged 26 homers over the next 12 seasons, he would have ended his career, at age 34, with 416 homers. But many observers think Tony C easily had 30-home run power, and he surely hadn’t yet entered his prime at the time he was beaned. It’s not hard to imagine Conigliaro playing into his late 30s. Had he averaged 30 homers a year for the next 14 seasons, and retired at age 36, Tony C would have amassed a total of 524 career homers.

Health is the key to longevity and that will always remain the greatest question in terms of what Tony C might have been. Five times he had bones broken by pitches, including the one that broke his shoulder blade in spring training in 1967, just five months before his career was tragically altered.

Tony C looked like a surefire Hall of Famer in-the-making, but it wasn’t meant to be. Though he was a star, he was also star-crossed. It could be said that Tony C was a shooting star. As Petrocelli said of his friend, the only thing he didn’t have was luck.

After his baseball career ended, Conigliaro worked as a sportscaster, first at WJAR in Providence, RI, and later at KGO-TV in San Francisco. He then worked as a sports agent for Dennis Gilbert in Los Angeles. Gilbert said that Conigliaro had been prescribed blood-pressure medication, but that he didn’t like to take it.

After visiting his family in Boston during the Christmas holidays, the 37-year-old Conigliaro was on his way back to Los Angeles when he suffered a heart attack on Jan. 9, 1982. He was riding with his brother, Billy, on the way to Logan Airport. Billy sped to Massachusetts General, the nearest hospital, but Tony was in a coma by the time they reached the emergency room.

Doctors said Conigliaro’s brain was deprived of oxygen for 14 minutes. He remained in a coma for weeks and required constant care for the next eight years.

Tony C passed away from kidney failure on February 24, 1990, at the age of 45.

However, his legacy lives on. Since 1990, MLB annually hands out the Tony Conigliaro Award, given to a deserving player for overcoming adversity.

Former Red Sox lefty Jon Lester earned the award in 2007, after being diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and successfully resuming his career.

It’s hard to imagine a bigger, brighter, more charismatic young star on the Red Sox roster since Tony C. Fred Lynn and Nomar Garciaparra may be the only Red Sox stars to burst onto the scene with such talent, charisma and popularity.

Tony C’s star shined oh so brightly, but all too briefly.